For years, every government has told us that crime is falling — and technically, they’re right. The long-term trend from the mid-1990s shows a sharp drop in violent crime, burglary and car theft. The once-dreaded high-crime Britain of the early Blair era is, statistically, a safer place.

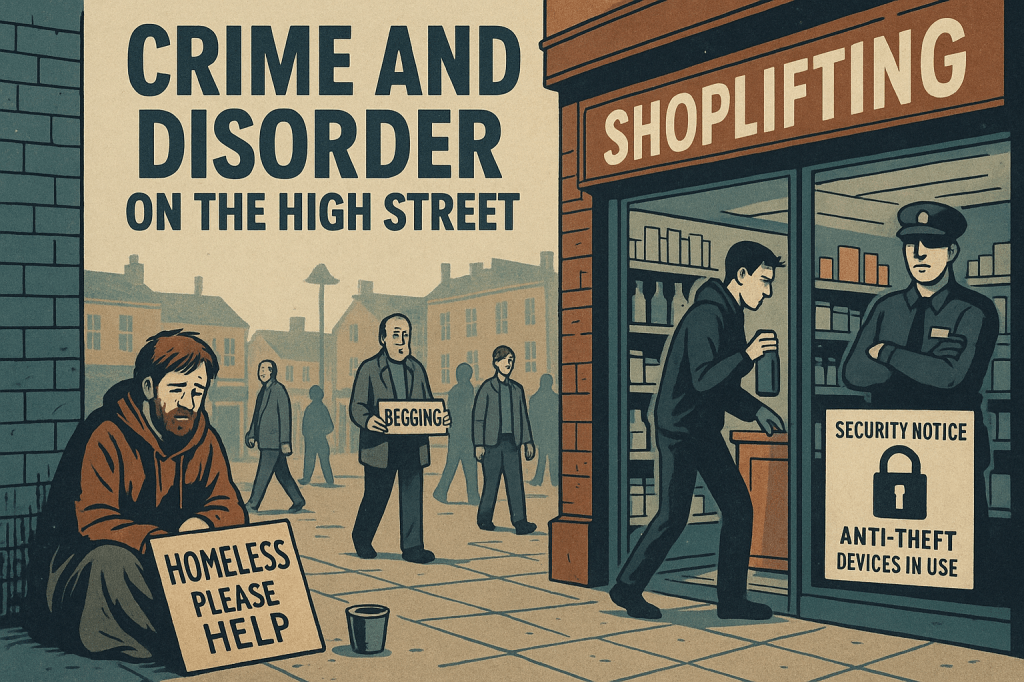

And yet, millions of people walk through Britain’s town centres and feel something else entirely: a creeping sense that the place has gone to pot. They see shuttered shops, tent encampments outside empty Debenhams, security guards patrolling the toiletries aisle, and groups of people clearly struggling with addiction or homelessness. The official line says things have improved. Reality — or at least what feels like reality — often says otherwise.

This divide between crime rates and the experience of disorder is now at the centre of a political storm. Ministers call it “perception.” Critics call it “gaslighting.” But a closer look at the data suggests something more nuanced: people aren’t imagining it. Certain forms of disorder really have worsened — significantly. Just not always the ones politicians want to talk about.

Homelessness: the return of what we thought we’d solved

Rough sleeping fell sharply in the late 1990s and early 2000s. But since 2010, it has surged again. Academic and parliamentary briefings show rough sleeping in England has risen by over 160% compared with 2010, only just below its recent peak. The tents, makeshift bedding and visible destitution that now line many urban centres are not nostalgia or “feelings” — they are a documented reversal of earlier progress.

For a public that lived through the more orderly town centres of the 2000s, the contrast is stark. No wonder people feel their high streets are fraying.

Begging and street disorder: political football, practical problem

Begging itself is difficult to measure, but rough sleeping and begging correlate tightly. The historic clampdowns of the 1990s (backed by the old Vagrancy Act) removed much of it from view. Today’s more humane — and more stretched — approach often means far greater visibility of extreme poverty on the streets.

Politicians routinely turn begging into a moral debate. But for ordinary people walking through town, it registers simply as evidence of decline.

Shoplifting: the numbers the government cannot spin

If there’s one area where the public’s instincts are undeniably correct, it’s retail crime.

Police-recorded shoplifting has soared to two-decade highs, rising from around 340,000 offences in 2023 to well over 500,000 by early 2025. Retailers say the real figure is closer to 20 million thefts a year, with a surge in violence and abuse against staff.

This isn’t “media hype.”

This is what drives the locked cabinets, the body-worn cameras, the behind-plastic-cheese aisles that make British shops feel like airport duty-free in a collapsing republic.

Ordinary people see this — and understandably conclude that something is seriously wrong.

Antisocial behaviour: the perception gap that isn’t entirely imaginary

ASB is notoriously subjective. Teenagers hanging around were considered normal in 1998; by 2008 they were rebranded “antisocial”; by 2025 they are a political storyline. But while overall ASB is difficult to trend cleanly, the label itself has grown so powerful that nuisance behaviour now feels like part of a wider breakdown.

Academic studies consistently show a gap between actual crime and fear of disorder — but they also show that visible signs of decay (graffiti, litter, street drinking, rough sleeping) strongly drive fear of crime. Britain now has more of those visible signs than at many points during the 2000s.

So is Britain safer or more disorderly? Uncomfortably, it’s both

The long-term crime drop is real.

But so is the rise in the forms of disorder that ordinary people actually encounter on the high street.

For most people, the issue isn’t whether homicide is down 40% or whether burglary is half the 1995 rate. What they see is:

More homelessness

More street addiction

More visible mental health crises

More retail theft and security theatre

More shuttered units and depleted town centres

It’s no surprise they conclude that “the country is going to the dogs.”

And, in the specific context of British town centres, they have a point.

The political mistake: blaming the wrong things

This is where the political rhetoric falters. Instead of addressing structural causes — housing scarcity, addiction services, mental health funding, local authority collapse, retail decline, and organised shoplifting — it is easier for politicians to shout about:

“Woke councils”

“Soft policing”

“Migrant beggars”

“Youth disorder”

Those make good headlines, but they don’t solve the underlying problems.

We’ve already seen what works:

Housing First programmes cut rough sleeping dramatically in the 1990s and again temporarily during COVID.

Neighbourhood policing reduces fear of crime and improves order, but requires investment.

Addiction and mental health services reduce the cycle of visible disorder that dominates town centres.

Retail crime partnerships (police + shops + councils) have shown measurable effects where properly funded.

None of these are new ideas. They’re just the ones that work.

If Britain wants safer, cleaner town centres, it has to stop performing politics and start solving problems

The irony is that the public’s perception is dismissed as “panic,” yet it tracks closely with the areas where the data genuinely show deterioration. People can sense when a place is fraying long before ministers admit it.

The challenge now is political courage:

to acknowledge that the high street disorder people see is real, but the causes are deeper than the headlines suggest.

Blaming the wrong targets is easy.

Fixing the right problems is hard — but it’s been done before, and it can be done again.