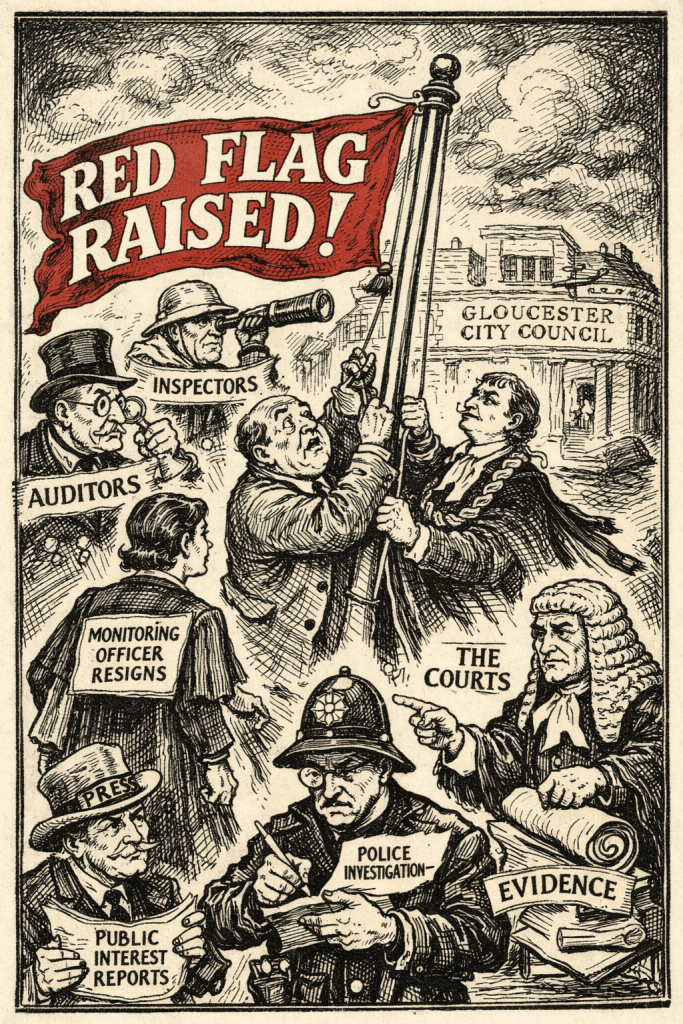

For more than a year, Gloucester City Council has been grappling with a growing list of current and historical problems — from disputed financial assumptions and budget gaps, to questions about governance, record-keeping, and how warnings were handled when risks first emerged. Against that backdrop, trust in the council’s internal checks and balances has been steadily eroded, both publicly and within professional local-government circles.

It is in this context that the resignation of the council’s Monitoring Officer takes on real significance.

When a Monitoring Officer leaves after a year, professionals across local government read it as a red flag, not a footnote.

It suggests deep governance stress, unresolved legal risk, and a failure to heed independent legal advice. And it tends not to be the end of departures — merely the first that matters.

At Gloucester City Council, this is not a routine staffing change. The Monitoring Officer is a statutory officer — the council’s legal conscience — appointed under the Local Government and Housing Act 1989 to ensure that decisions are lawful, constitutional processes are followed, and standards of conduct are upheld. Where illegality or serious maladministration is suspected, the Monitoring Officer has a legal duty to intervene, including issuing a formal report that compels the authority to stop and publicly address the issue.

Solicitors do not leave such roles lightly, particularly not after only a year in post. In practice, early resignations usually point to one or more of three factors: inherited governance failures that prove impossible to resolve internally; sustained resistance to legal challenge from senior officers or political leadership; or an unacceptable level of personal professional risk.

That risk is not theoretical. Monitoring Officers carry individual responsibility. If advice is repeatedly ignored, overridden, or marginalised; especially where governance failures continue or records are questioned the exposure sits with the named officer, not with the abstract notion of “the council”. At that point, remaining in post can jeopardise professional standing and regulatory compliance. Leaving becomes an act of professional self-preservation.

There is also a misconception that resignation draws a line under scrutiny. It does not. A former Monitoring Officer can still be called upon in external audits, public interest reports, regulatory reviews, or court proceedings. In some respects, they may be more able to speak freely once removed from internal pressures.

For governance professionals, this is why such departures matter. They are signals — not of a problem resolved, but of one that has reached a critical point. History suggests they are rarely isolated events.

The question Gloucester now faces is not simply why a Monitoring Officer has gone, but what conditions made it untenable for the council’s statutory guardian of legality to remain. That question will not disappear with her departure.