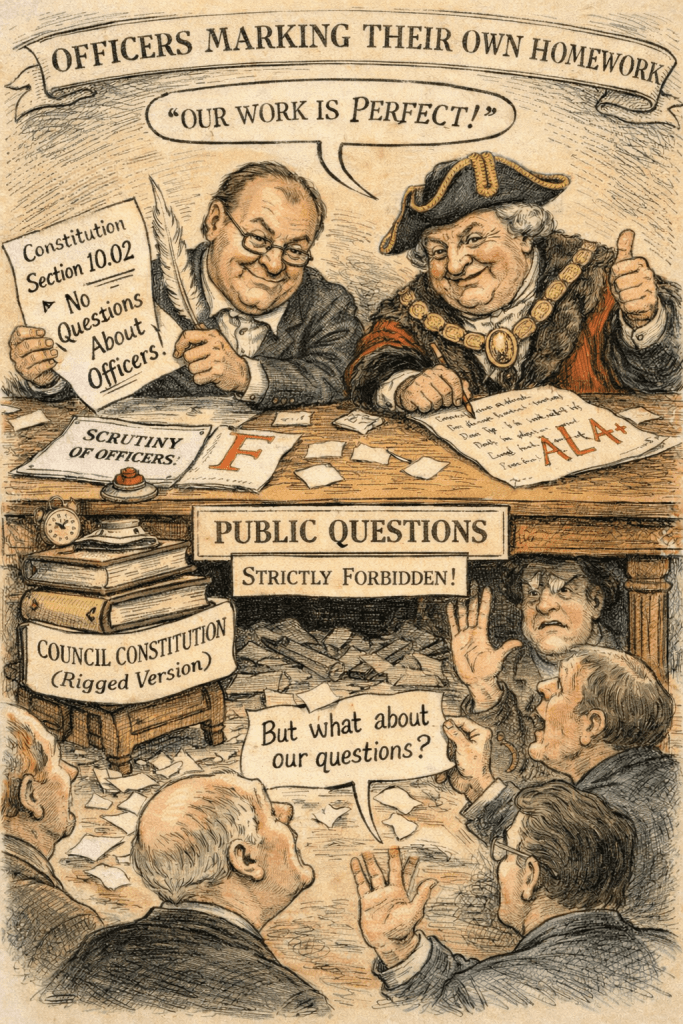

In any functioning democracy, public scrutiny is not a nuisance to be managed—it is the point. Yet in Gloucester, recent events suggest that accountability is being treated less like a civic duty and more like a procedural inconvenience.

Following the revelation of a £17.5 million financial black hole, Gloucester City Council convened an emergency “public meeting” on 18 December. On paper, this appeared to be a moment of openness: residents invited to ask questions; democracy seen to be done. In practice, it was anything but.

Questions relating to the actions of senior officers were explicitly ruled out. Legal threats were aired—towards members of the public and councillors alike. The effect was unmistakable: a warning shot across the bows of anyone tempted to probe too closely.

A Constitution That Controls the Conversation

Under Gloucester City Council’s constitution, the Head of Paid Service, acting in consultation with the Mayor, has the power to:

Reject public questions outright

Edit questions for “form and brevity”

Reorder, group, or reframe questions

Decide what is—and is not—admissible

This goes far beyond basic moderation. In many comparable local authorities, admissibility tests are tightly drawn, procedural in nature, and overseen by independent statutory officers such as the Monitoring Officer. Crucially, questions about official actions, governance decisions, and the exercise of statutory powers are explicitly permitted.

Gloucester’s model is different—and troublingly so.

The Conflict at the Core

The constitution allows questions to be excluded if they concern the “personal affairs or conduct” of officers or members. That wording might sound reasonable—until you look closer.

In practice, it risks conflating private life with professional conduct, and shielding senior decision-makers from legitimate scrutiny over how they have exercised public power. When questions about governance, financial oversight, or statutory responsibility can be ruled “inadmissible” by the very officer whose conduct may be in question, the problem is obvious.

This is not merely poor optics. It is a structural conflict of interest.

The same individual who may be the subject of public concern helps decide whether questions are heard at all, can soften or reframe questions before they reach the chamber faces no independent appeal or review of those decisions.

Where senior officers also hold multiple statutory roles, power becomes dangerously concentrated—and scrutiny correspondingly diluted.

Why This Matters

Free speech in local democracy does not mean shouting abuse from the public gallery. It means the right to ask difficult, well-founded questions about how public money is managed and how authority is exercised.

A system that filters those questions through the very people being questioned does not protect good governance—it undermines it. It replaces accountability with choreography. It turns public meetings into managed performances, not forums for truth.

At a moment when trust in public institutions is fragile, Gloucester’s constitutional arrangements send exactly the wrong message: that scrutiny is something to be controlled, not answered.

If democracy is to mean anything at all, referees cannot also be players—and those entrusted with power cannot be allowed to decide whether they may be questioned about how they used it.